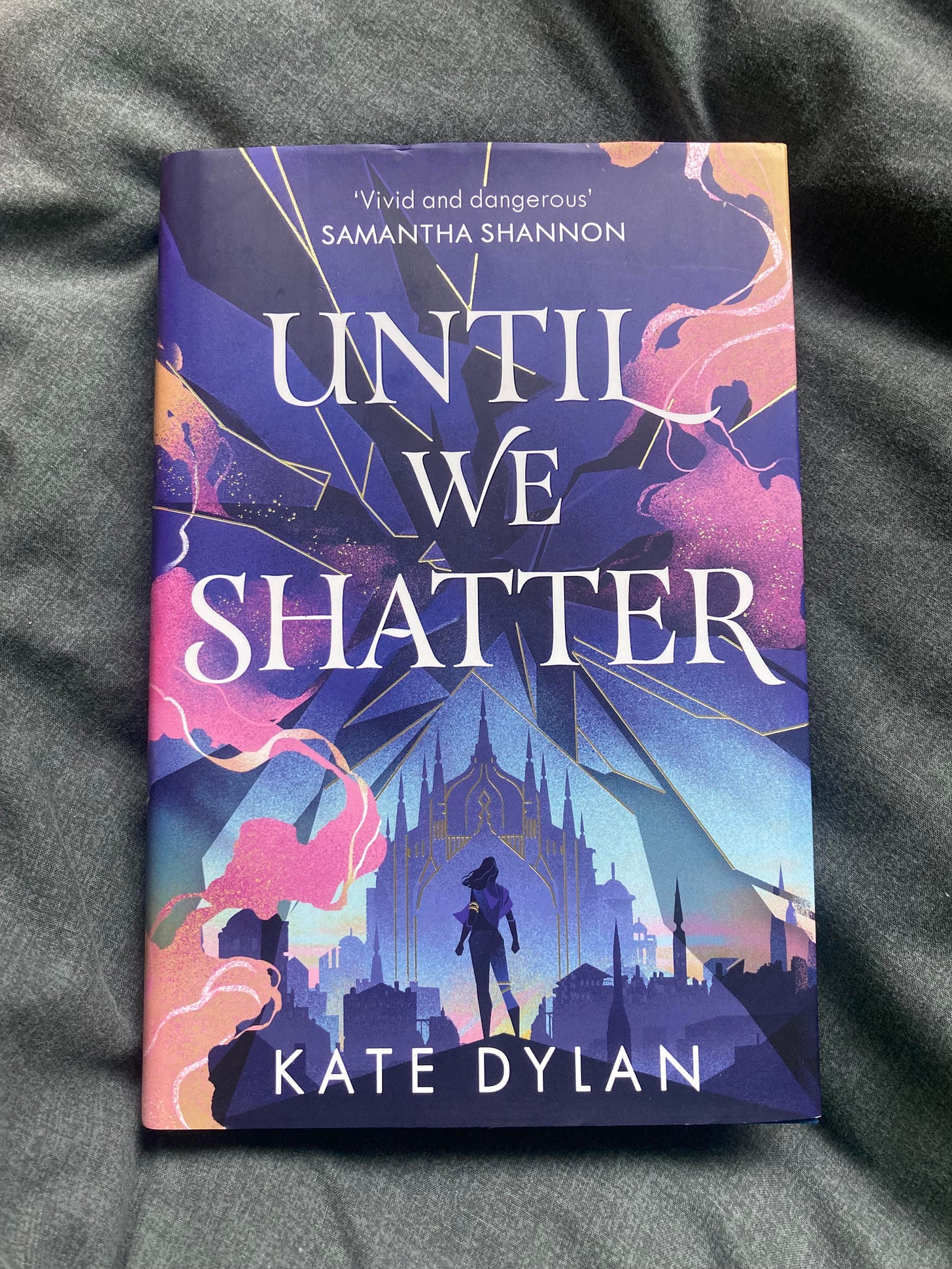

Book Review: Until We Shatter

February's post is a review of Kate Dylan's debut fantasy novel Until We Shatter.

I picked up Kate Dylan’s fantasy debut Until We Shatter because I loved her science fiction Mindwalker duology. Those books were full of thrill and action, exploring teenagers rebelling against oppressive, capitalist institutions and exploring the boundaries of their romantic and platonic relationships. I don’t read much YA fiction, but like with Mindwalker, the plot of Until We Shatter drew me in. A fantasy heist novel? Yes please.

Cemilla Constance lives a life of thieving to pay for her mother’s medical treatment. Her magic makes this easy—in this world, magic is the ability to transport into the ‘Grey’, a shadow world unseen by the non-magical ‘typics’. A person’s type of magic is defined by colour, and whilst full-blood magic ‘Shades’ are protected by their Council, the magic-diluted ‘Hues’ (those with Shade and typic parentage) are persecuted by both the Council of Shades and the typic Church. Hues, like Cemilla, also face another threat—the Grey resists their presence, and if they make a mistake, their bodies will shatter like glass. Cemilla faces all this danger when she and her friends are roped into a heist under the threat of a Shade who could sell them out to the Council if they refused: they must break into the Church and steal something kept under strict protection.

There’s action, tension, and twists…. everything is not as it seems, as we slowly learn more about the Shade orchestrating the heist, the new Hues that join them, and what is really being hidden by the Church. Friendships are strained and broken apart by betrayal, but Until We Shatter also highlights the importance of found family. Cemilla, Ezzo, Eve, and Novi are Hues who had lost parents to the Council’s punishment of Shade-typic relationships; traumatised and alone, they found each other and took care of each other. They set up their own sanctuary in, ironically, an abandoned monastery. For the heist to succeed, they need a ‘purple’ Hue (each colour has a different magical ability); enter Lyria, who hid her powers from her typic family and had never met another person like herself before.

The theme of persecution is something I recently wrote about in my review of The Moonstone Covenant, which similarly features a hatred of magic in a city ruled by non-magical people. Until We Shatter adjusts this for a slightly younger audience, but the existence of magic is still used to explore the oppression of minority groups and how it’s rooted in fear. I interpreted the colour magic as an allegory for queerness, and Dylan’s novel explores the impact of discrimination on young adults specifically, which is an important perspective given the impact that LGBTQ+ oppression in the US is having on queer teenagers.

That this persecuted rainbow of Hues find each other is queer kinship— the way that LGBTQ+ people create bonds of love and care beyond heteronormative and biological family structures, especially when forced out of those families. There are queer relationships within the group—Cemilla and Novi have a history, and there’s a kindling spark between Novi and Lyria—but their bond goes beyond that. They understand each other, as Hues, more than any Shade or typic could. Even Cemilla, whose Shade mother is still alive, faces judgment at home: her mother wants her to hide her Hue, albeit to keep her daughter safe from harm, so Cemilla can only be herself in secret, with her friends. When her mother discovers that she has been using her magic, Cemilla is told to leave the house and never come back. Being kicked out of the family home for coming out or being discovered as queer is all too common an experience for LGBTQ+ people.

One thing that really added to this sense of kinship is how the rest of the group respond to Lyria’s deafness. At first, Novi is the only one in the group that can use sign language to communicate with her, but the others take small actions such as facing Lyria when they are speaking so she can read their lips. Cemilla realises that they can use knowledge magic to learn sign language quickly, with the recognition that this is still an easy option that required little effort from the group. I think this is done well, as Dylan incorporates specific signs that are used by the characters. It’s a nice bit of disability representation, and a reminder that people (and society) should make an effort to be accommodating.

There’s also a complexity to the protagonists as they realise that violence is necessary to their survival; violence not dissimilar to that which they themselves have experienced. While morally controversial, violence has usually been part of revolutionary movements. For Frantz Fanon, anti-colonial violence was justified (though violence for violence’s sake was not to be celebrated). In Until We Shatter, Cemilla and her friends aren’t part of a revolution, but violence becomes necessary to end the threat coming from their oppressor (a threat to themselves personally, and to the safety of the whole city). This violence sn’t excused, but there’s the recognition that ‘this world makes a violence of us all’ (p.304). The book is the first of two novels set in this world—I’m hoping the second will feature more of a revolution against the oppressive Council and Church. After reading Until We Shatter, I’m excited for what the next book will bring to this fictional world.